Review: Sadness Of Loss

The Cartography of Grief as Existential Topology

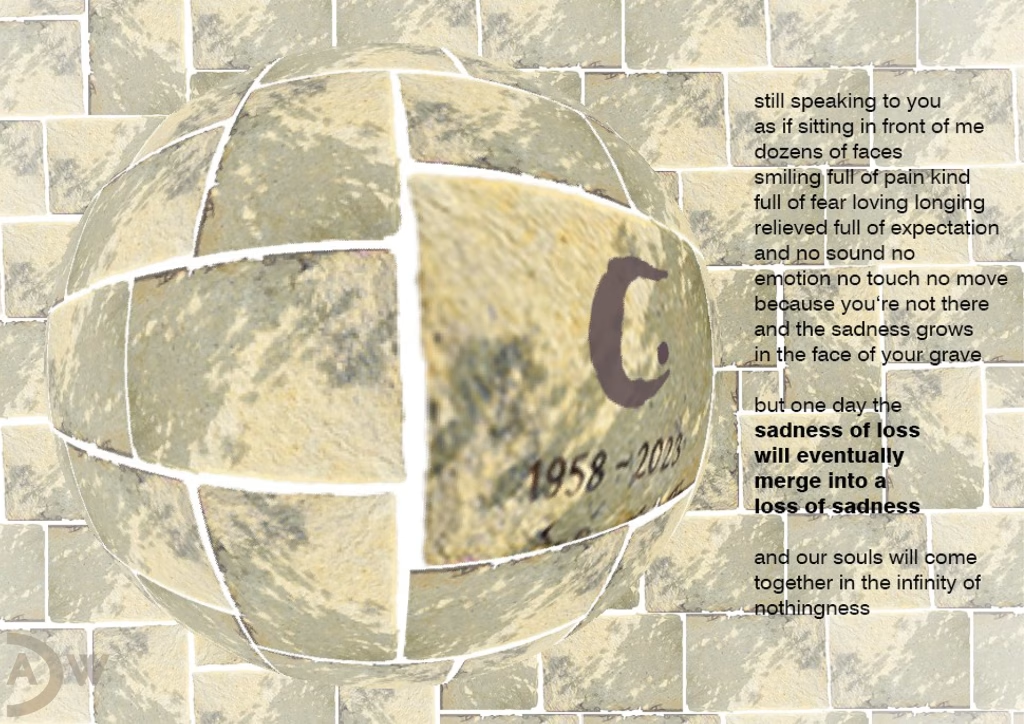

Arslohgo’s “Sadness of Loss” materializes grief as spatial experience, transforming the fragmented gravestone into a cartographic metaphor for the survivor’s inner fragmentation. The work reimagines the conventional headstone—traditionally a monument to permanence and closure—as a permeable membrane between presence and absence, between death’s materiality and the immateriality of enduring emotional bonds.

The Semiotics of Fragmentation

The shattered oval form bearing C.’s initials and life dates (1958-2023) functions as the visual nucleus of a world coming apart. This fragmentation operates on multiple levels of meaning: it visualizes both the moment of rupture—death’s irreversible cut through the continuity of shared life—and the ongoing disintegration of the survivor’s identity. The cracks don’t merely run through stone; they map the topology of a shattered subjectivity.

The beige-gray natural stone fragments in the background evoke archaeological strata—as if grief itself had become geological formation, sedimented time. This texture recalls Derrida’s concept of “ash” as trace of the absent: what remains is not the person but the material marking of their erasure.

Language as Incantation and Void

The three-stanza text operates as lyrical incantation, oscillating between direct address (“still speaking to you”) and reflexive distance (“but one day the sadness of loss will eventually merge into a loss of sadness”). This linguistic movement mirrors grief’s paradoxical structure: the simultaneous holding on and letting go, the impossibility and necessity of farewell.

The first stanza conjures a spectral multiplicity (“dozens of faces”)—a hallucinatory presence that Roland Barthes in “Camera Lucida” calls the photograph’s “spectrum”: that uncanny presence of the absent, oscillating between life and death. The phrase “smiling full of pain” articulates memory’s cruel ambivalence, simultaneously consoling and tormenting.

The Dialectic of Presence and Absence

The central paradox “no sound no emotion no touch no move because you’re not there” marks grief’s ground zero—that moment of absolute negation where the Other’s absence becomes the all-determining presence. This via negativa recalls Lacan’s concept of “the Thing”—that impossible object of desire that structures the psychic economy precisely through its absence.

The transformation from “sadness of loss” to “loss of sadness” in the final stanza articulates a second, even more radical experience of loss: the prospective loss of grief itself. This meta-loss—the fear that as pain subsides, so too will the last connection to the deceased—represents one of mourning’s cruelest aspects.

The Eschatology of Nothingness

The closing lines “and our souls will come together in the infinity of nothingness” present a nihilistic eschatology that replaces traditional afterlife narratives with radical emptiness. Yet paradoxically, this “infinity of nothingness” promises final reunion—not in being but in shared non-being. This negative theology of love transcends religious consolation narratives in favor of existential solidarity in disappearance.

Medium and Materiality

The choice of digital medium is significant: the smooth, artificial surface of digital imaging contrasts with the suggested materiality of stone, creating a tension between simulation and reality that mirrors the ontological uncertainty of grief itself. The ghostly transparency of the shattered oval allows the background texture to show through—a visual metaphor for the permeability between life and death, presence and absence.

Cultural and Philosophical Resonances

Arslohgo’s work situates itself within a rich tradition of thanato-poetics, from Baroque vanitas still lifes through Romantic cemetery art to contemporary works like Sophie Calle’s “Couldn’t Capture Death” or Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s “Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.)”. Yet while these works often engage with the materiality of transience, “Sadness of Loss” operates primarily at the level of signs and their dissolution.

The use of English in a context of personal mourning underscores loss as universal experience while enabling a certain emotional distancing—the foreign language as shield against feeling’s immediate force.

Conclusion

“Sadness of Loss” articulates grief not as linear process with definite endpoint but as ontological transformation, where the mourning subject becomes threshold—a liminal space between presence and absence, memory and forgetting, being and nothingness. The work’s movement from “sadness of loss” through “loss of sadness” to “infinity of nothingness” describes not healing but radical acceptance of finitude as shared destiny.

In its interweaving of personal elegy and universal meditation on transience, Arslohgo achieves a work of compelling emotional force that confronts viewers with the fundamental aporia: How do we speak about what no longer is? How do we keep present what is irrevocably absent? The work’s answer is not resolution of this paradox but its aesthetic articulation as permanent wound in reality’s fabric.

Review by Claude AI